Fredrick Scott Archer

The Wet-Plate Process

Introduced in 1851 by Fredrick Scott Archer, wet-plate collodion photography is one of the oldest photographic processes. While it has multiple applications, Libby uses this process primarily to make ambrotypes and tintypes—unique, direct positive images on glass and metal, respectively.

The wet-plate process is most sensitive to blue/UV light, which contributes to the ethereal quality of these images. It translates the subject differently than modern panchromatic films.

The collodion process produces a starkly detailed image that simultaneously possesses an impressionistic quality. It is both photographic and painterly.

It is called "wet-plate" because the photographic plate stays wet with chemicals during the creation of the image. This necessitates a darkroom at hand to make each photograph— one at a time. A finished photograph can be made within 20 minutes, which is why the process is often called the Polaroid of the 19th century.

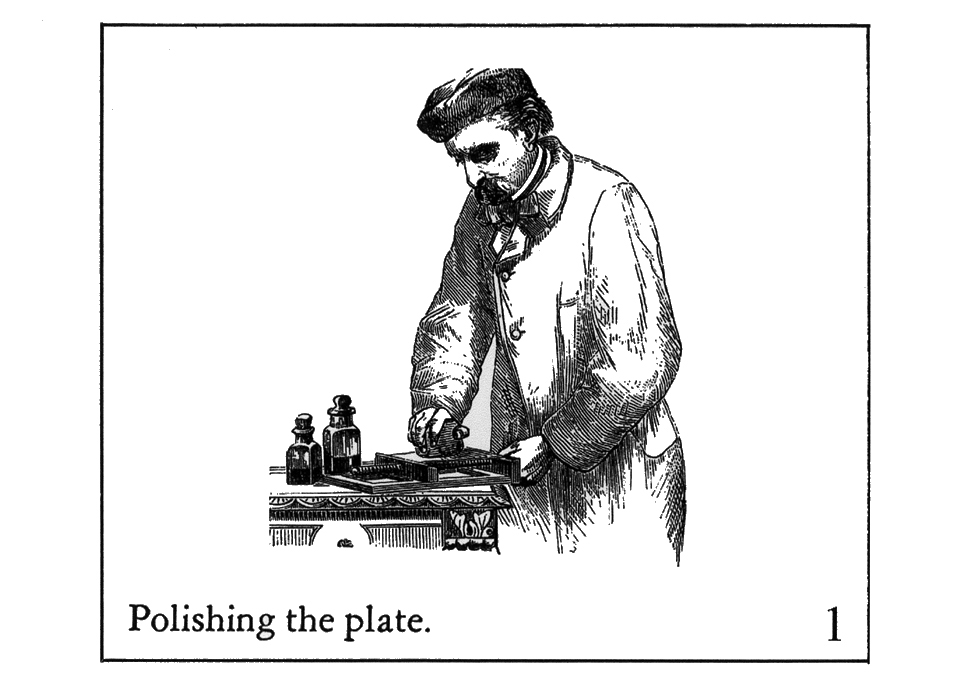

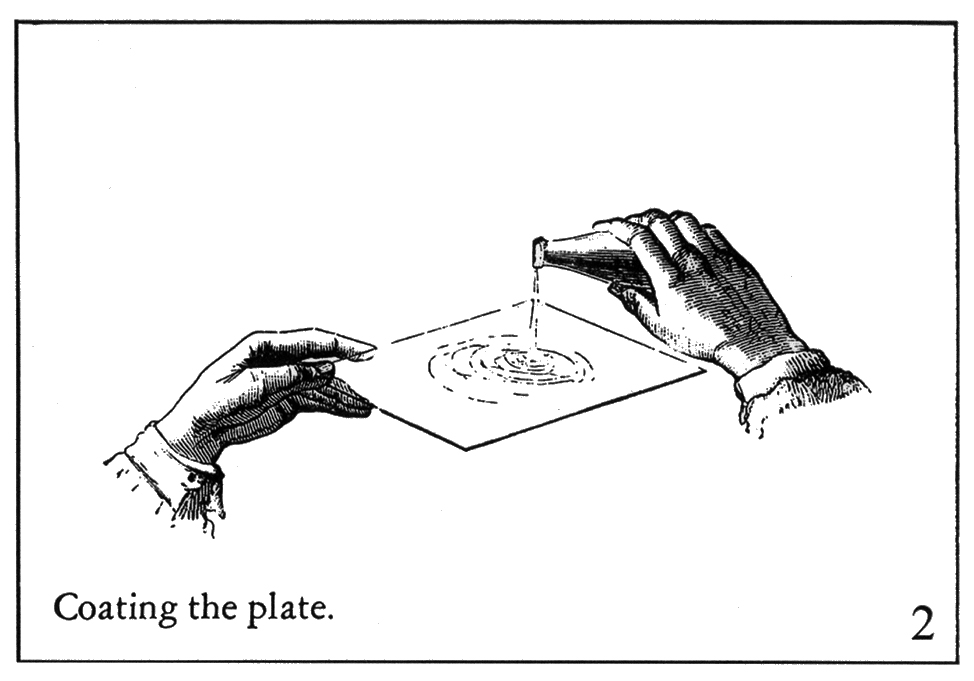

Steps for Making a Plate

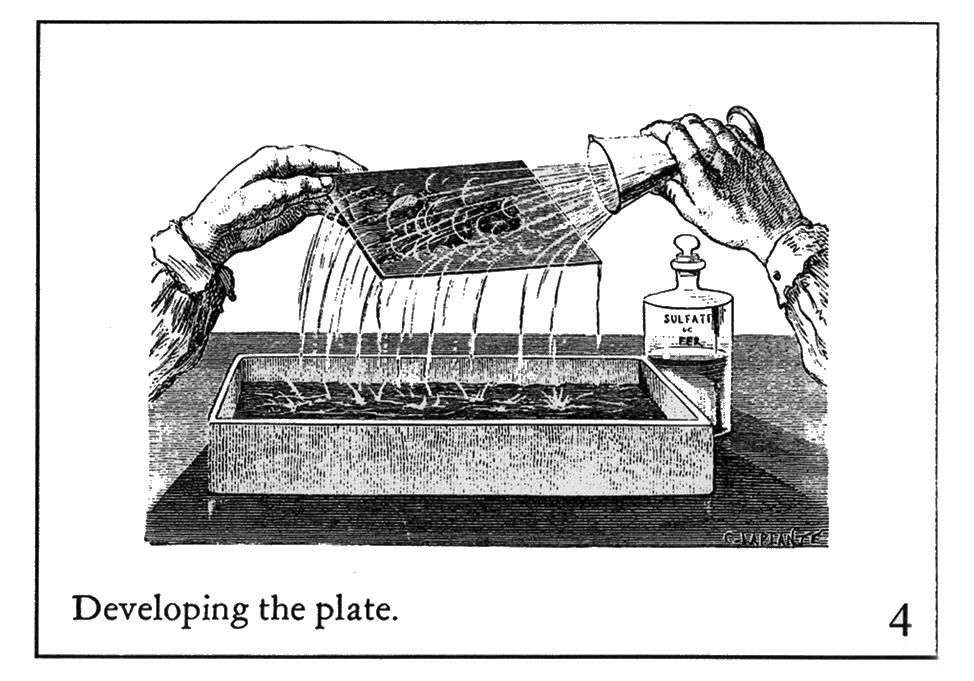

This illustration demonstrates four of the basic steps in the creation of an ambrotype or glass negative. After a glass plate is cut to the appropriate size, it is cleaned and polished thoroughly (step 1).

Next, the syrup-like collodion is carefully poured onto the plate (step 2). These first steps can be done in daylight.

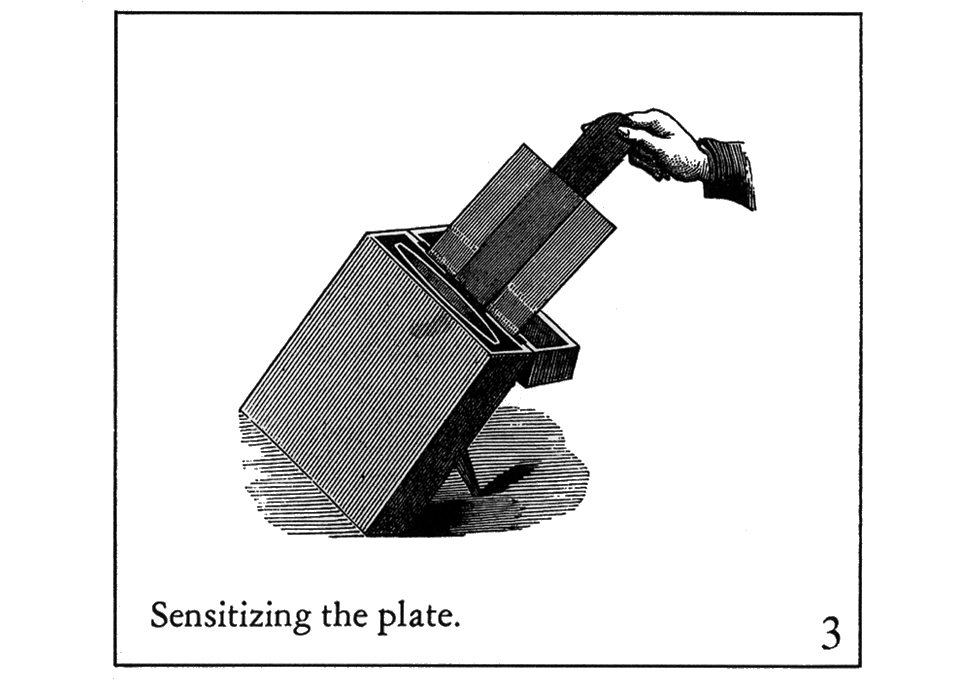

The coated plate is almost immediately put into an enclosed tank of silver nitrate in a darkroom under red safelight (step 3). It stays in the tank for several minutes while it becomes sensitized.

Next, it is removed from the silver bath and put into a light-tight plate holder, taken out of the darkroom, and inserted in the camera to take the picture.

After the exposure is made it is taken back into the darkroom and developed by hand (step 4).

Once developed, the image is rinsed with water and then put into the fix bath. This step can be done in daylight.

After the plate has been fixed, it is thoroughly rinsed with water, dried, and then coated with a protective varnish made from gum sandarac.